Auschwitz I

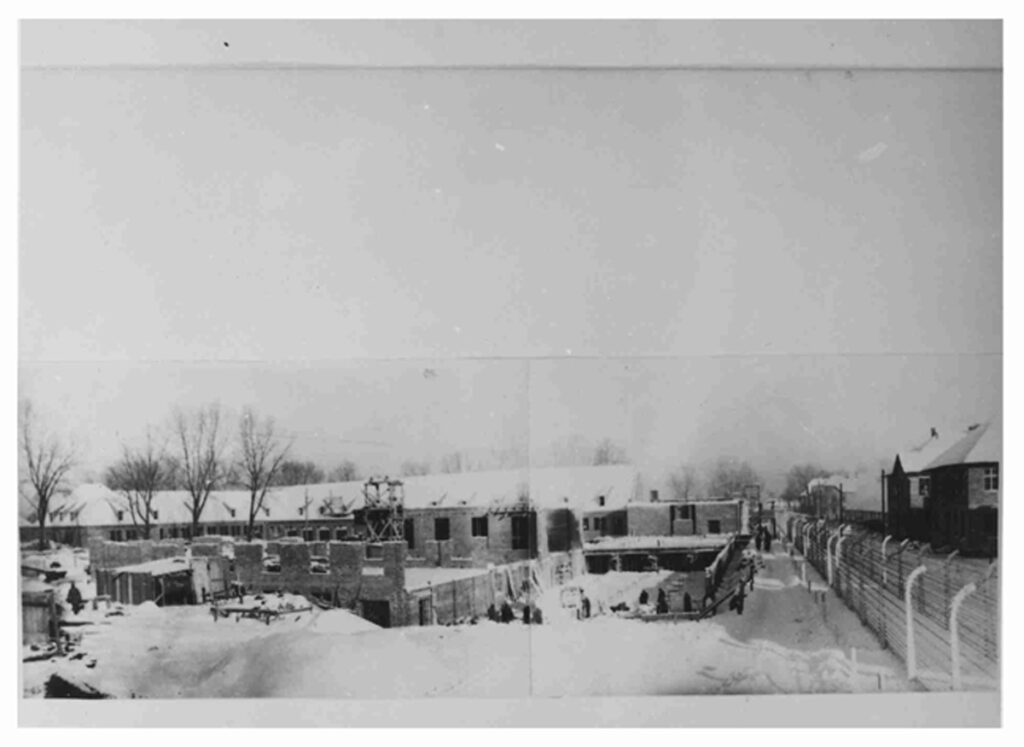

In April 1940, Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler ordered the creation of a concentration camp at a Polish barracks in Auschwitz. It initially functioned as a prison for Polish resistance fighters. But Himmler was keen to exploit their labour too, so in late 1940 he created the Interest Zone (Interessengebiet) – a 40 km2 agricultural estate to the south of Auschwitz.

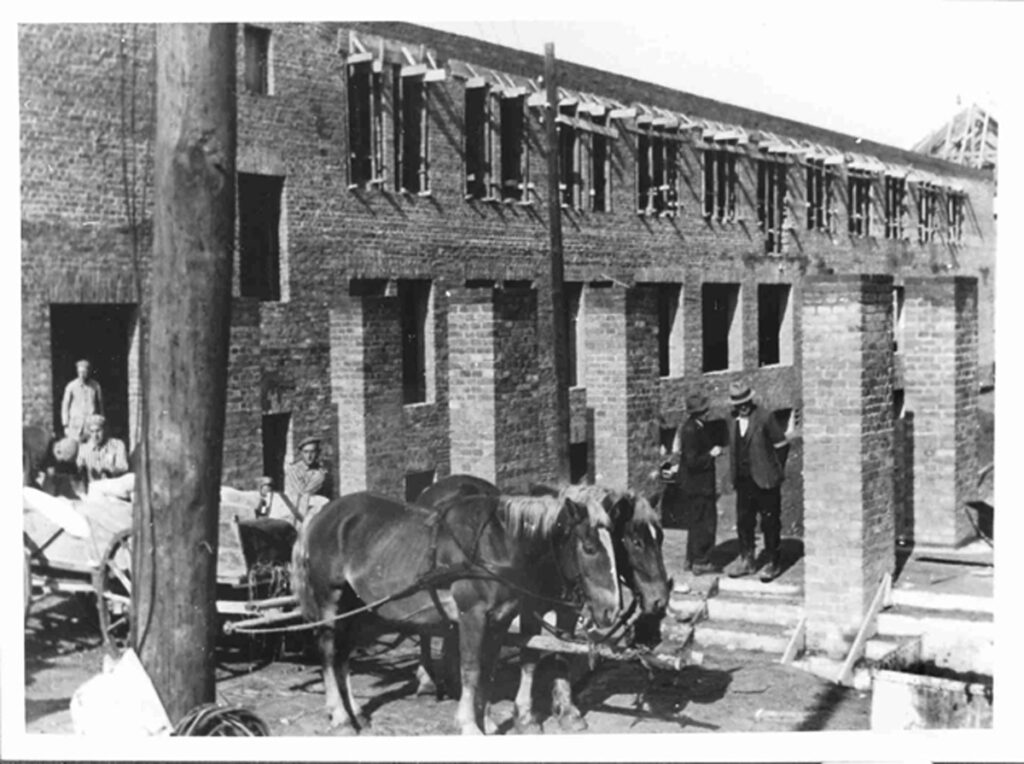

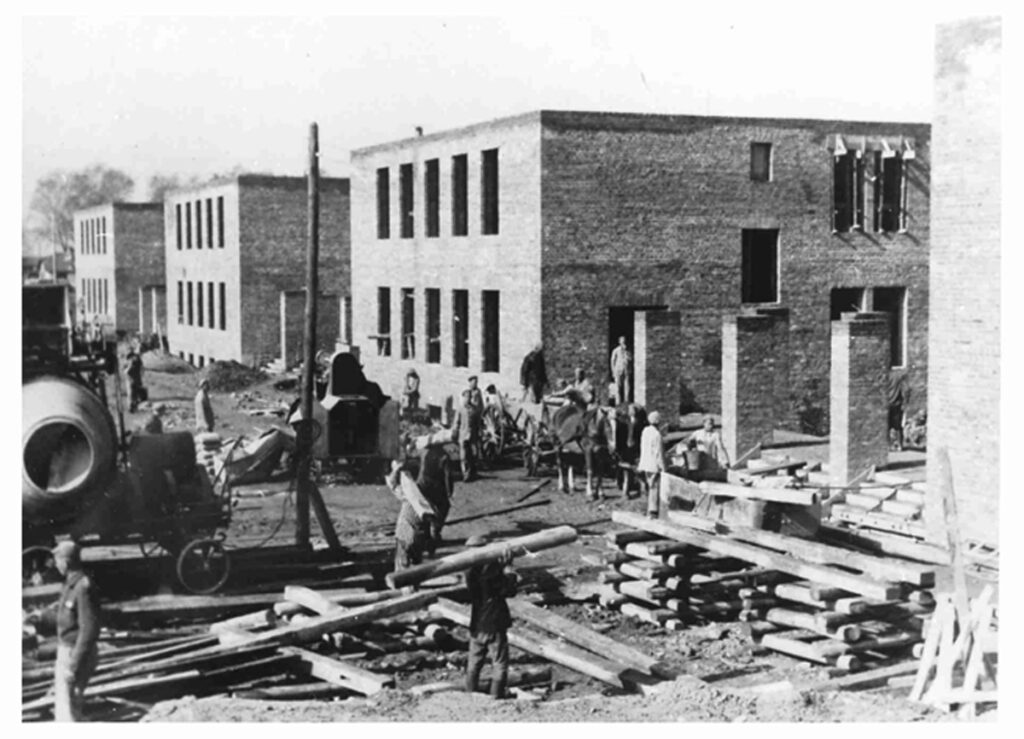

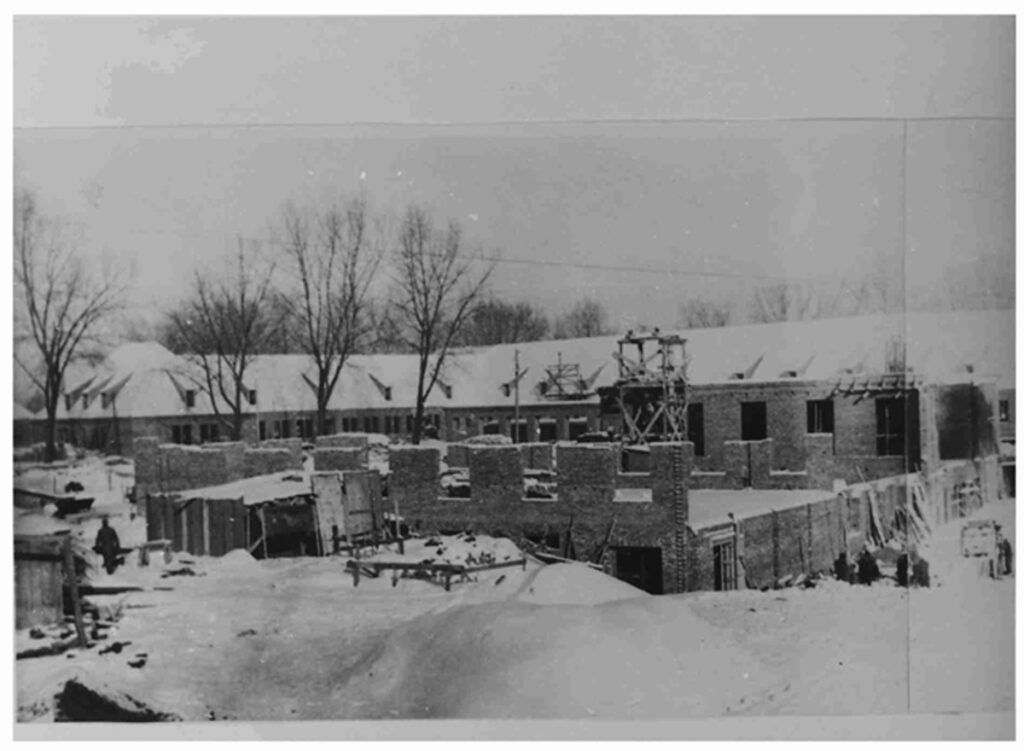

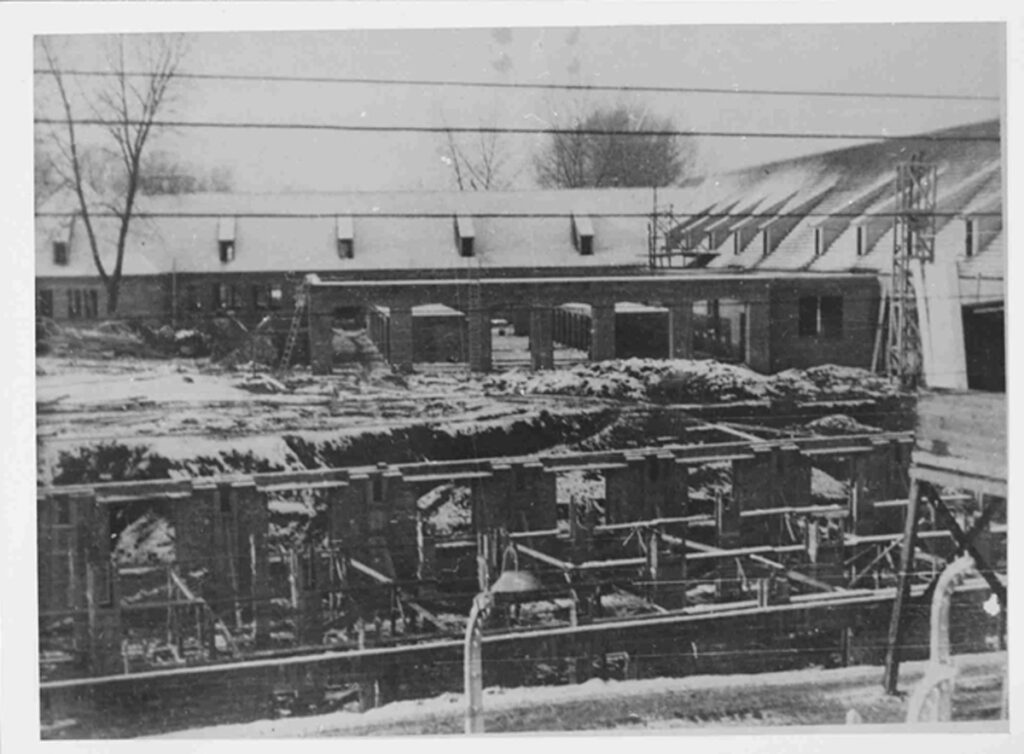

In 1941 IG Farben decided to build a synthetic rubber factory at Auschwitz and signed a contract with the SS: the chemical company was granted permission to ‘use’ prisoners, while the SS was provided with the resources it needed to expand the original camp (Auschwitz I) and construct a new one for 125,000 people. The village of Brzezinka (Birkenau in German) was duly swallowed up. Russian prisoners of war were initially intended to provide the slave labour at Auschwitz II-Birkenau.

In 1941 IG Farben decided to build a synthetic rubber factory at Auschwitz and signed a contract with the SS: the chemical company was granted permission to ‘use’ prisoners, while the SS was provided with the resources it needed to expand the original camp (Auschwitz I) and construct a new one for 125,000 people. The village of Brzezinka (Birkenau in German) was duly swallowed up. Russian prisoners of war were initially intended to provide the slave labour at Auschwitz II-Birkenau.

Living and working in the camps

The concentration-camp system was collective and privacy was unknown. Work was intended as the basic instrument for the ‘re-education’ and ‘training’ of camp inmates.

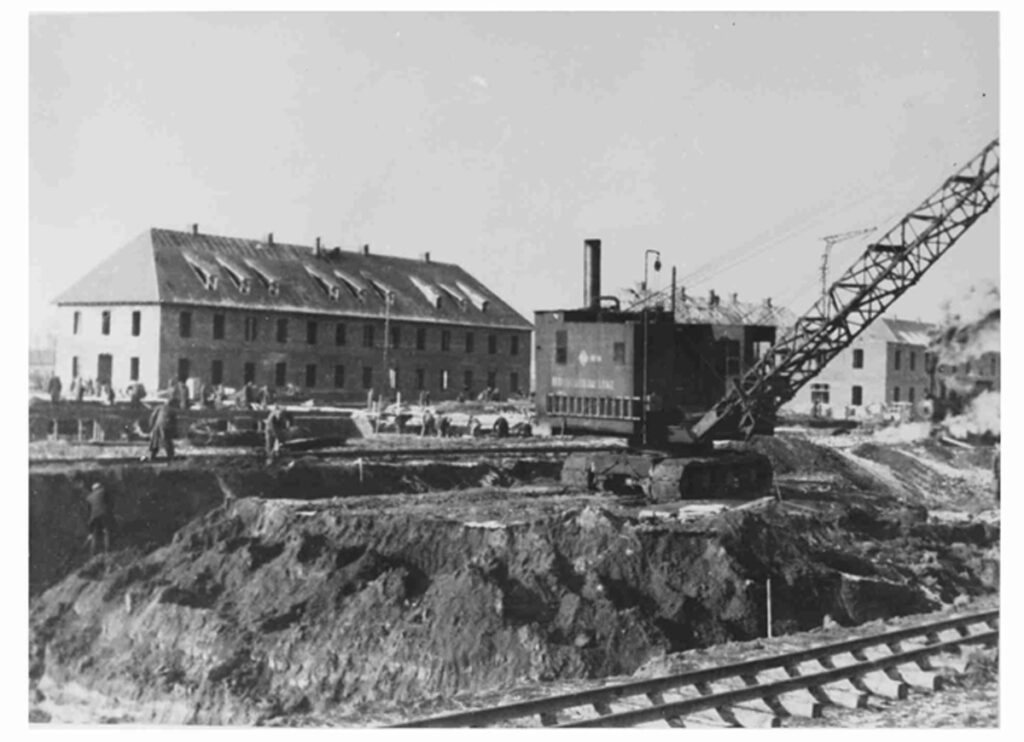

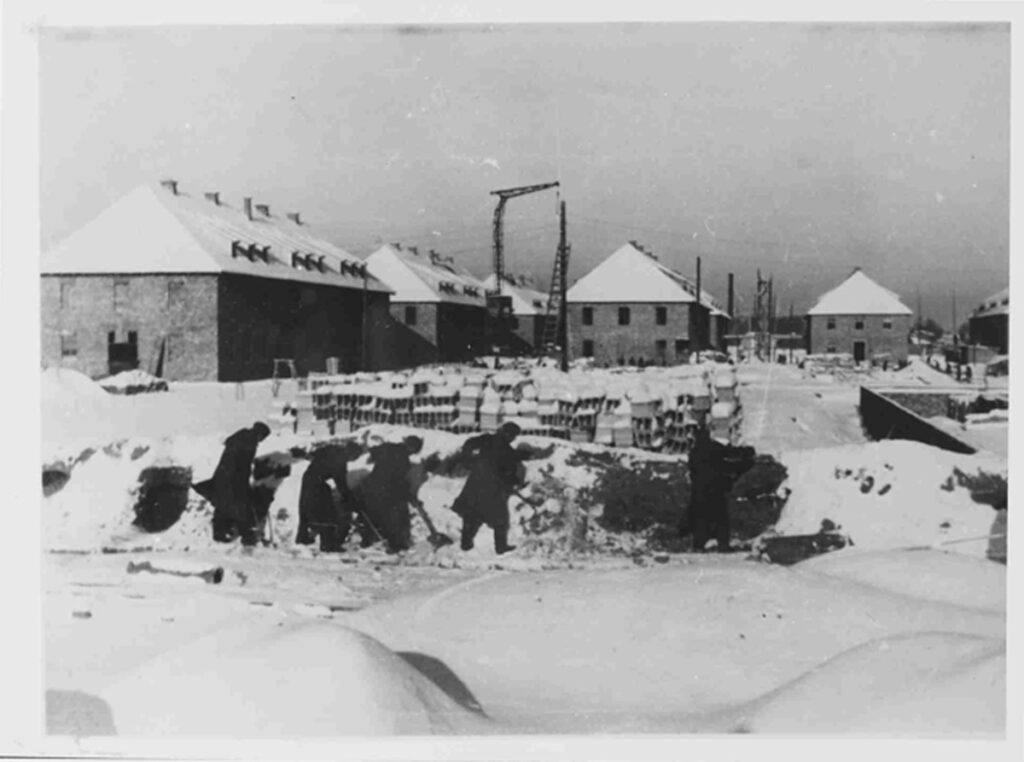

In the early days at Auschwitz, in particular, a great deal of pointless work was carried out. Prisoners were

forced to perform labour that was often too onerous for them, while constantly being harassed by the

guards. They dug drainage ditches and foundations, and were made to drag heavy rollers. Needless to say, the work was done without any kind of protective equipment or clothing.

Tourism

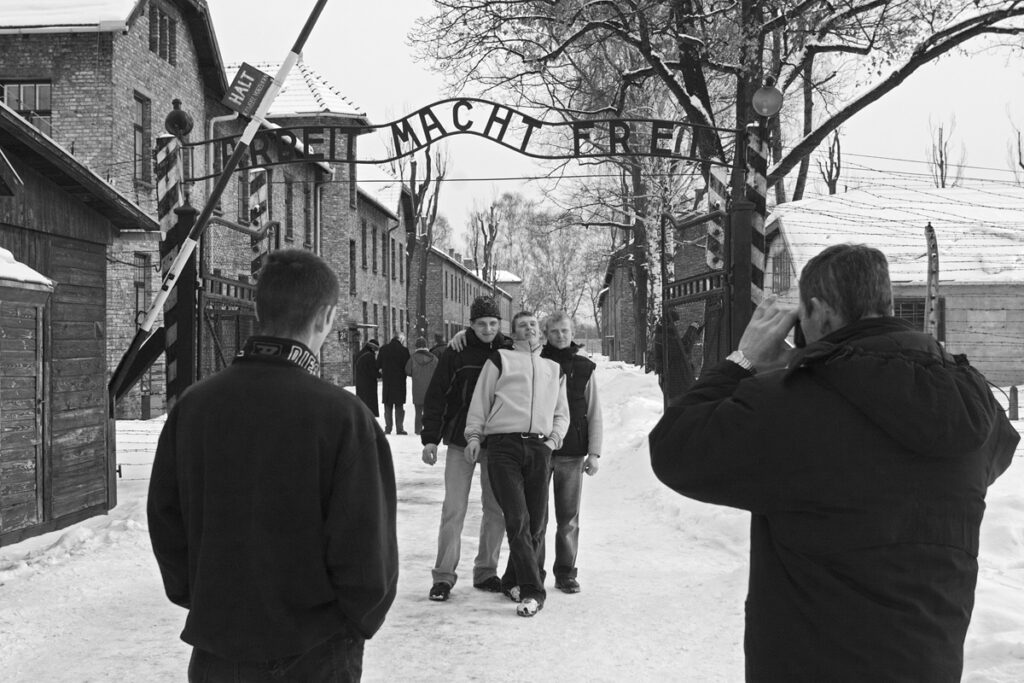

Over two million people visited the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum in 2018. Arbeit macht Frei, the motto

above the ‘gate’, is generally thought of as the portal into hell. In reality, the iconic gateway had become an

internal structure after the camp’s expansion in 1941. The fence at the parking lot was the camp’s real

entrance. After completing their tour, virtually all the visitors get back into their car or coach and leave. Few visit the town of Oświęcim. The Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum has been incorporated in the Cracow tourism

circuit.